Exactly a year ago from today, one of us wrote a short piece entitled “Will Housing Save the U.S. Economy?” The conclusion was pessimistic:

“we need to temper our optimism on what a housing recovery can do. I agree that house prices will continue to rise and new residential construction will steadily increase from its current very low level … But we will not be returning to the boom years that preceded the Great Recession. The days when housing was the predominant force driving economic activity are gone…”

With an additional year of data, the prediction from a year ago seems spot on. Let’s take a closer look.

Rising house prices could potentially boost economic activity through two channels. First, and most importantly in our view, it could allow lower income, lower credit score households to borrow money and spend. This has been historically called the “housing wealth effect,” but the “home equity withdrawal effect” is a more appropriate term. As our latest research shows, the housing wealth effect is driven entirely by lower income households who borrow against rising home equity to spend. This channel was huge during the 2002 to 2006 period, something our research quantifies.

Second, it could potentially boost construction activity through a standard investment channel. If prices rise while costs remain the same, then builders have an incentive to build more homes, which directly contributes to GDP. Also baby boomer financial statistics show that many retirees end up downsizing their homes so they can live off of social security benefits.

We can test whether we are getting a big kick from house price growth by comparing the last two years to the two years prior to the Great Recession. House price growth in both periods was similar. In fact, as the chart below shows, house prices grew even faster over the last two years relative to the earlier period:

So house prices grew strongly from 2011 to 2013. Did it boost household spending through the home equity withdrawal channel? Here is a comparison of the total amount of cash-out refinancing done in 2005 and 2006 versus 2012 and 2013. A cash-out refinancing is when a homeowner refinances her mortgage with a larger principal balance, hence taking cash out of the home:

In 2005 and 2006, homeowners refinanced over $600 billion in mortgages where cash was taken out. The chart above actually understates the 05-06 total amount considerably, because we are using Freddie Mac data that includes only prime conventional mortgages. The most aggressive borrowing took place in Alt-A and sub-prime markets.

What about the 2012 and 2013 period? There was a much smaller volume of cash-out refinancing. Despite home values rising more from 2011 to 2013 than from 2005 to 2006, homeowners took much less equity out of their homes compared to the earlier period. While this doesn’t directly measure spending, our research shows that almost all spending during the 2005 and 2006 period came out of active home equity withdrawal. So the fact that there has been very little cash-out refinancing in 2012 and 2013 tells us that there is likely very little spending out of housing wealth currently.

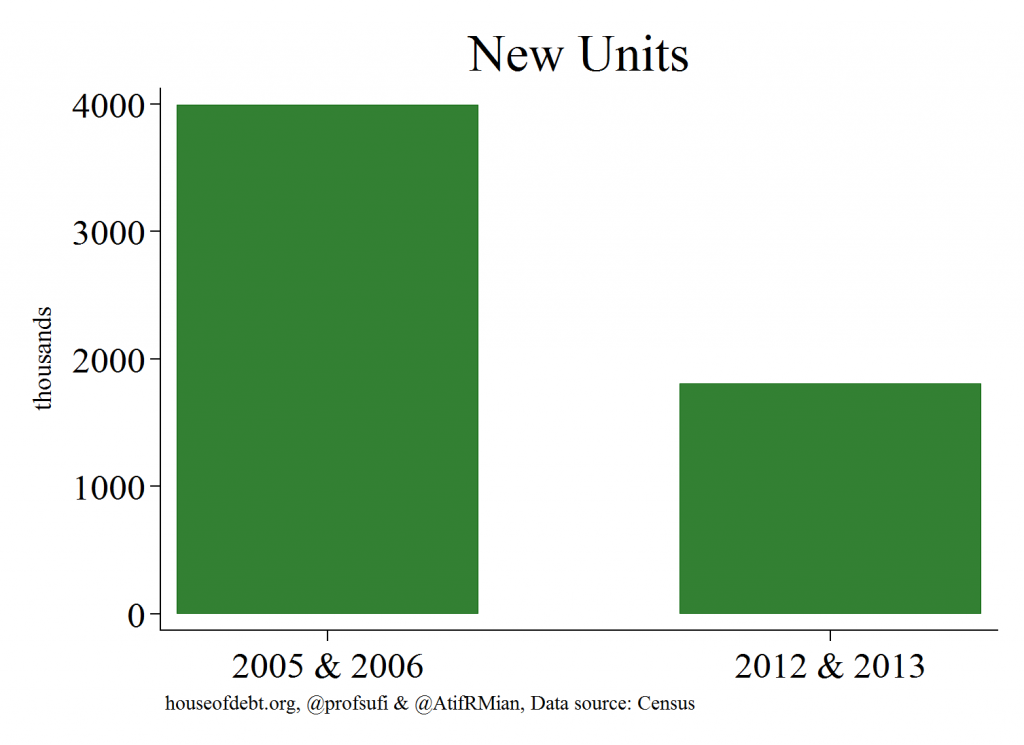

What about construction? Have builders responded to higher house price growth by building more homes? Here is the chart comparing 2005 and 2006 with 2012 and 2013:

In 2005 and 2006, almost 4 million buildings were built in response to rising home values. In 2012 and 2013, the number was less than half that amount. Home builders have not been responding to rising home values nearly as aggressively as they did prior to the Great Recession. The building channel of higher house prices is muted considerably.

Dreadful new home sales data yesterday heightened concerns that house price growth will stall. but we are making a different point: the sensitivity of economic activity to rising house prices is much lower today than it was prior to the Great Recession. This is due to a number of factors, such as the rise in investor purchases and the fact that the households who would be most likely to spend out of housing wealth are no longer homeowners. In fact, rising rents may dampen economic activity.

Ironically, the fact that house price growth has not contributed much to overall economic activity over the past few years implies that the economic consequences of stalled house price growth may be small. Slower house price growth will lower new residential construction, but it has been pretty weak anyway. And cooling the rapid rise in rents may actually help boost spending on other goods. The bottom line is that the U.S. economy will have to look for an engine other than housing to drive growth going forward.

UPDATE: This great Business Insider interview with Jed Kolko at Trulia makes a similar point about renters. As he says: “Rents, however, rose throughout the recession or fell only modestly, depending on the measure you look at, even though incomes stagnated, and of course low mortgage rates don’t help renters.; The recession caused rental demand to rise. Millions of people lost homes to foreclosure, and many of them became renters; in addition, many others put off their first-time home purchase and remained renters.”

We think it is officially time to stop cheering for higher house prices. They aren’t having much of an impact on the economy anyway, and the resulting higher rents are hurting many.